Cahawba’s Black Community

By 1860, 64% of Cahawba’s population was African American. In Dallas County, three out of four persons were black, yet often the history that is recorded reflects the white minority that owned the newspapers, ran the banks, voted and was elected to office. The bulk of historical data we have from Cahawba reflects those in power-but that tells only a small part of Cahawba’s story.

By 1860, 64% of Cahawba’s population was African American. In Dallas County, three out of four persons were black, yet often the history that is recorded reflects the white minority that owned the newspapers, ran the banks, voted and was elected to office. The bulk of historical data we have from Cahawba reflects those in power-but that tells only a small part of Cahawba’s story.

Prior to the Civil War, the majority of blacks were forced to endure the backbreaking labors of fieldwork. A few were freed, but even those could not live in town without a white guardian. And while a few could carry a gun, none were allowed out at night after the market bell rang. Still, many became such highly skilled craftsmen that they eventually could purchase their freedom. These enslaved laborers became bricklayers, carpenters, blacksmiths, and plasterers. Many learned how to read and write prior to emancipation Curiously enough, blacks entirely controlled Cahawba’s poultry business.

After emancipation, records finally begin to appear recognizing the civic contributions of Cahawba’s black community. Many citizens played prominent roles fighting for hard-won political freedom. Many became landowners, including the Lightnings, Lattimores, Arthurs and others. Jordan Hatcher, Cahawba’s postmaster, was appointed to the Constitutional Convention. Tom Walker was one of Alabama’s first state legislators and became a highly successful lawyer in the District of Columbia, as well as a trustee of Howard University.

After emancipation, records finally begin to appear recognizing the civic contributions of Cahawba’s black community. Many citizens played prominent roles fighting for hard-won political freedom. Many became landowners, including the Lightnings, Lattimores, Arthurs and others. Jordan Hatcher, Cahawba’s postmaster, was appointed to the Constitutional Convention. Tom Walker was one of Alabama’s first state legislators and became a highly successful lawyer in the District of Columbia, as well as a trustee of Howard University.

When the county seat was removed to Selma in 1866, Cahawba’s prominence was at the end. By 1870, the number of blacks dwindled to 302 while the overall population stood at 431. By this time, Cahawba became known as the “Mecca of the Radical Republican Party,” a derogatory nickname given by Selma residents since the deserted, half-destroyed courthouse became a rallying point for freedmen attempting to solidify the moderate political gains they had secured during Reconstruction.

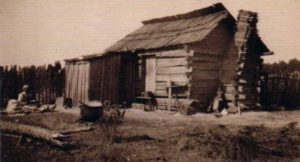

As the years passed, the town of Cahawba dwindled further. The local black community built a school themselves from salvaged materials for local children. It sat adjacent to St. Pauls African American Methodist Episcopal Church — a building which had earlier served as a temporary school house. Today, the school is one of only three structures still standing at the Old Cahawba site.

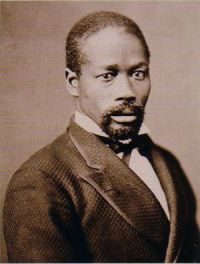

Congressman Jeremiah Haralson

Born in 1846, Jeremiah Haralson was self-educated and was the only African American to serve in the Alabama House, Alabama Senate, and the U.S. House of Representatives. Known for his dynamic speaking, in 1876 Haralson was arrested during his campaign for re-election by his Democratic opponent, the sherriff of Dallas County, General Charles M. Shelley. Though Shelley failed to carry any of the majority black district, he never-the-less “carried” the district, and went to Washington. After this incident, reconstruction was clearly over in Dallas County.

Born in 1846, Jeremiah Haralson was self-educated and was the only African American to serve in the Alabama House, Alabama Senate, and the U.S. House of Representatives. Known for his dynamic speaking, in 1876 Haralson was arrested during his campaign for re-election by his Democratic opponent, the sherriff of Dallas County, General Charles M. Shelley. Though Shelley failed to carry any of the majority black district, he never-the-less “carried” the district, and went to Washington. After this incident, reconstruction was clearly over in Dallas County.

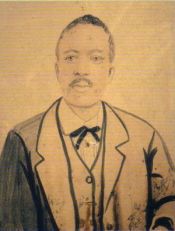

Ezekel Arthur, Successful Farmer

Ezekel Arthur, a freed slave, became a successful farmer and eventually purchased the Fambro House — one of the few remaining structures at Old Cahawba. The Arthur family owned the home until it was recently purchased by the state.

Ezekel Arthur, a freed slave, became a successful farmer and eventually purchased the Fambro House — one of the few remaining structures at Old Cahawba. The Arthur family owned the home until it was recently purchased by the state.

Illustrations courtesy of the Alabama Historical Commission. Historic photographs courtesy of the Alabama Department of Archives and History.